Four Namibian Master’s students spent six months at the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt (PTB) in Braunschweig last year. They were all interviewed during their stay in Germany, and this is what Rosamunde (Rose) Shilongo had to say.

Starting point

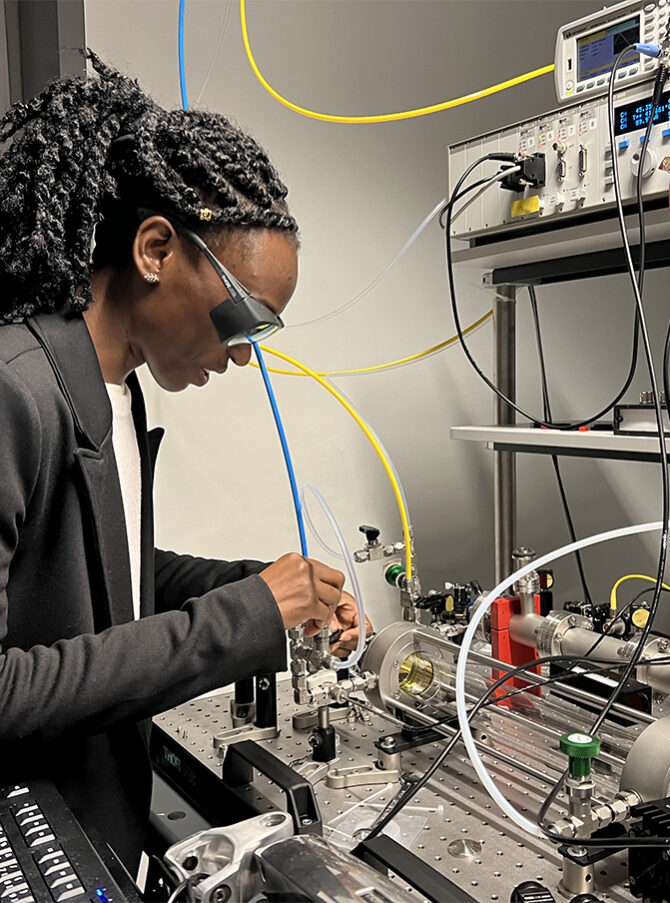

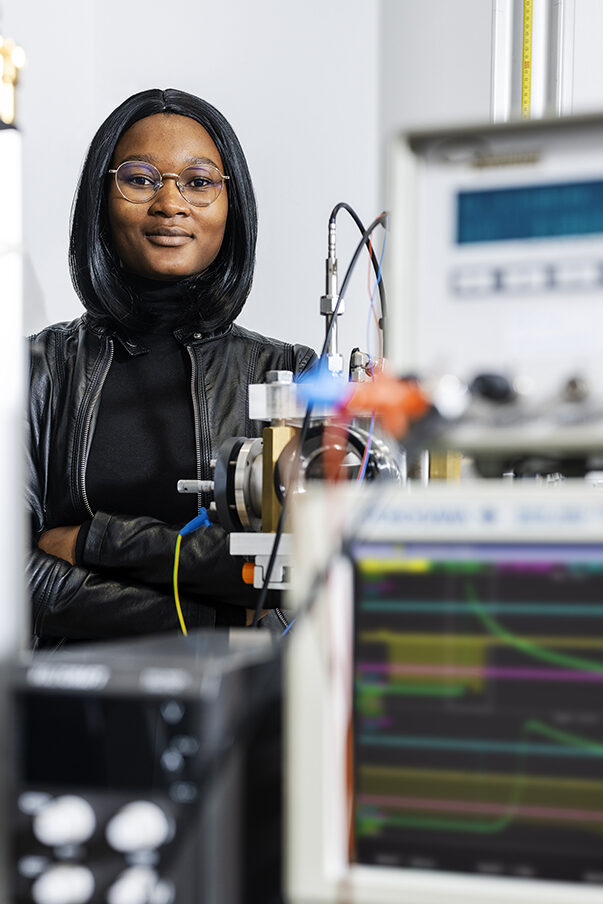

Rosamunde (Rose) Shilongo never thought she’d work on assessing hydrogen purity, but this electrical engineer from Namibia surprised herself last year. She mastered the art of using laser absorption spectroscopy in just a few weeks. This was within a research project advancing green hydrogen technologies. The research conducted at PTB was part of a Namibian-German scholarship programme for a Master’s in renewable energies. Emphasizing the environmental aspects along with safety and quality assessment meant she easily found the overlap between chemistry and engineering.

It was her lecturer at the University of Namibia (UNAM) who first drew her attention to the research topic. And Rose herself found out about the Green Hydrogen Scholarship Programme on LinkedIn. Rose, who was doing her post-graduate course at UNAM in Windhoek, had not expected to be directly involved with hydrogen purity. Working in PTB’s Physical Chemistry Department for six months changed her mind though.

Rose started learning German as soon as she handed in her application for the scholarship programme. She told Candela how that made her move to Braunschweig go smoothly. PTB helped with that too. Two staff members from PTB’s international section went to Namibia to meet all four of the Master’s students ahead of their arrival. They supported them with their paperwork and with practical issues, making the visitors’ first few days in Germany trouble-free.

Not many points of difference

When Rose was asked about the cultural differences between Germany and Namibia, she observed some similarities. One thing she and her fellow students did notice though was that Germans stare a lot. In some Namibian cultures, like hers in particular, it’s deemed rude to stare, whereas in Germany, not making eye contact might be seen as dishonest. It took all four Master’s students a while to realize that staring is a sign of interest. People aren’t looking at you because you have something on your face. They are staring because they like the way you look.

As far as the size of each country goes, Namibia is more than twice as large as Germany. But its population – at just under 3 million – is less than that of Berlin. Rose found the city of Braunschweig to be manageable in size. And after being asked about settling in, she stated that her landlord had been “wonderful” and that she had adapted to living in Germany well.

Another similarity Rose noticed was to do with food. The staples in Germany are pork and potatoes while in some Namibian cultures, particularly hers, they are beef and pap. She told Candela that pap is made of maize and sometimes millet meal. Having similar types of food helped her to feel at home quite quickly. Even the weather was not as different as she had envisioned – besides the wonderful rain – but that was probably because the group came to Germany in the summer.

Points of research

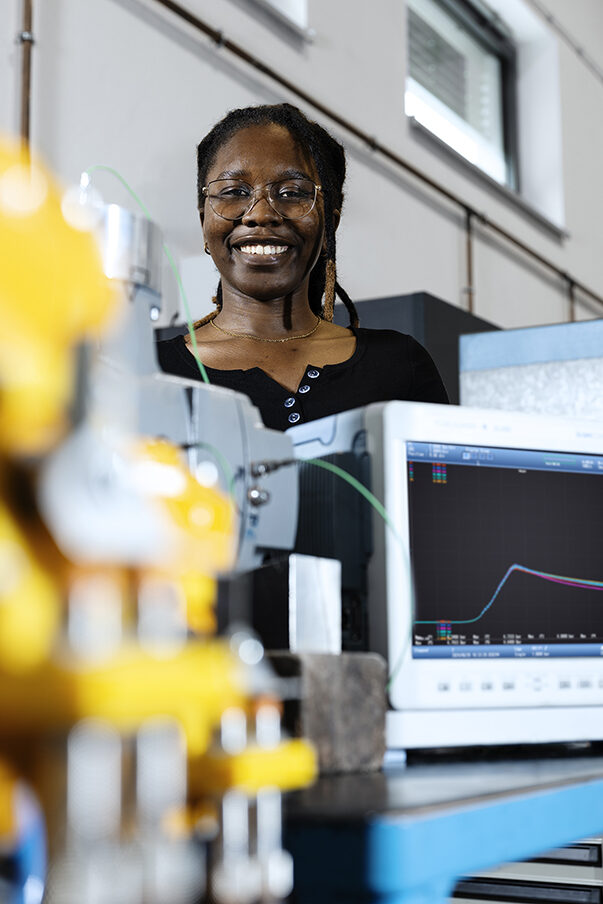

The interview then turned to Rose’s research project: hydrogen purity assessment using laser absorption spectroscopy. She explained that a narrow infrared laser beam is passed through a tube filled with hydrogen gas. As the light travels through the gas, hydrogen molecules absorb some of it at specific wavelengths. A detector on the other side measures the transmitted light, and the resulting absorption pattern reveals how much hydrogen is present in the sample. Each gas has its own unique absorption spectrum – like a fingerprint – which allowed Rose and her team to identify and quantify the hydrogen accurately.

She went on to explain that absorption patterns can change depending on pressure, which affects the shape and strength of the absorption lines. That’s an important detail, especially when it comes to trading hydrogen commercially, where precise purity levels matter. Rose gave an example: imagine using two different sensors to measure hydrogen purity. One gives a reading of 99%, and the other says 98%. Is there actually a difference in purity, or are the sensors just calibrated differently? Her work focuses on reducing these kinds of uncertainties by developing more accurate, traceable measurement methods and helping to standardize sensor calibration.

For Rose, the research goes beyond the lab. It connects with her passion for environmental sustainability, safety and quality assurance in the hydrogen industry. She admitted that jumping into the world of spectroscopy came with challenges – especially since her background is in engineering, not chemistry. But over the course of her six-month research stay, she picked up valuable lab experience and even learned to program in a new language, adding another practical skill to her toolkit.

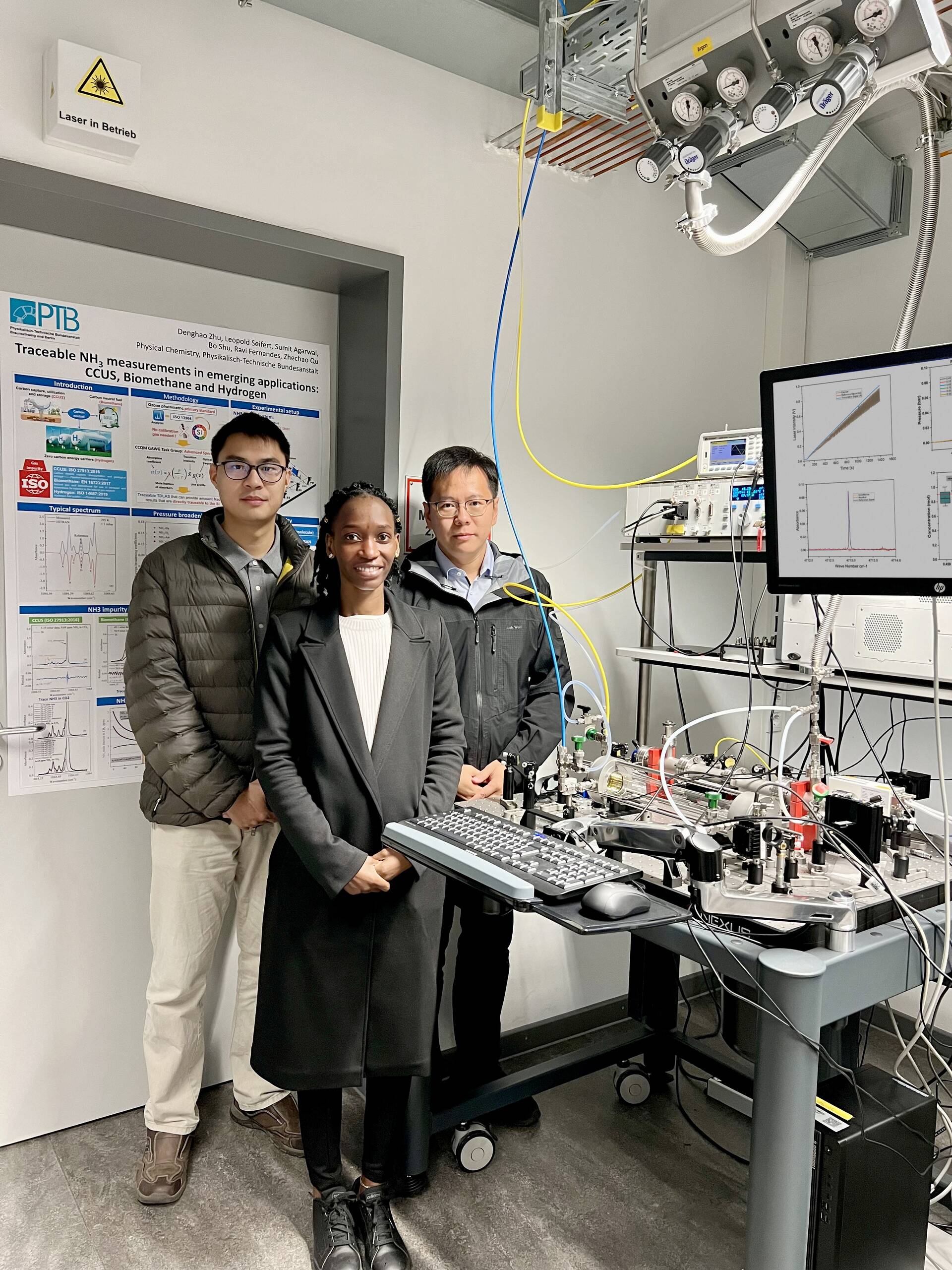

From left to right: Denghao Zhu (formerly PTB), Rose Shilongo (UNAM) and Bo Shu (PTB) next to a test setup for analysing hydrogen

Closing points

Rose found working with her supervisors and colleagues at PTB “wonderful”. She said they were always there when she needed them. They introduced her to the labs and made sure she felt comfortable working there. She particularly mentioned Denghao Zhu, who helped her with coding, Sumit Agarwal, who supported her in the lab along with Zhechao Qu and Bo Shu, who always made time to answer her questions.

As the interview drew to a close, Rose spoke about her plans for the future. Once she has completed her Master’s, she aims to enter a PhD programme and then become a lecturer. And she doesn’t rule out coming back to Germany and working here again. Perhaps we’ll see her advancing green hydrogen technologies even further in Africa or Europe one day. Whatever she ends up doing, we wish her all the best.

Interview conducted by Sabine Thomas, article by Ella Jones